From Regranting to Redistribution

How the Cultural Solidarity Fund Moved Money & Why We Need Community-Centered Coalitions

March 2024

Written by:

Sruti Suryanarayanan

with Emma Werowinski

Prepared for:

The Mellon Foundation

Edited and guided by: Haley Andres, Michelle Amador, Randi Berry, and Ximena Garnica

Cover Image: Emma Dulski

Report Design: Emma Werowinski

Copy Editing: Gideon Hess

The Cultural Solidarity Fund (CSF) is an initiative administered by IndieSpace (formerly Indie Theater Fund) with leadership by LEIMAY and a coalition of arts administrators and institutions that provides relief microgrants of $500 to artists and cultural workers including individual artists, administrators, production staff, custodians, art educators, ushers, guards, and more and prioritizes Black, Indigenous, People of Color (BIPOC), immigrant, disabled, d/Deaf, and trans and gender-nonconforming individuals who have been most severely impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic.

This evaluation report on the Cultural Solidarity Fund was made possible through a grant to LEIMAY (Cave Organization, Inc.) from the Mellon Foundation.

More Information: culturalsolidarityfund.org

How to Cite this Report: Suryanarayanan, Sruti and Emma Werowinski. “From Regranting to Redistribution: How the Cultural Solidarity Fund Moved Money & Why We Need Community-Centered Coalitions.” Cultural Solidarity Fund (March 2024).

Lead Researchers: Emma Werowinski and Sruti Suryanarayanan

Research Guides: Haley Andres, Michelle Amador, Randi Berry, and Ximena Garnica

This publication is covered by a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. To obtain permission for additional uses not covered in this license, please contact Emma Werowinski, Sruti Suryanarayanan, or the Cultural Solidarity Fund.

How did the Cultural Solidarity Fund execute over $1,000,0000 in relief grants to 2,030 individual artists and cultural workers across New York City?

By rooting in values, leaning on community, and leading with instincts.

As the COVID-19 pandemic began and the need for economic support grew, many support efforts emerged to meet the needs of organizations and individuals left floundering by the sudden shutdown. From state-developed programs, like the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act, to sector-specific initiatives, like the Shuttered Venues Operators Grant (SVOG), the world rose to meet a political opening1 and committed to providing relief.

When individual artists' and cultural workers’ needs weren’t met by these grants, other members of the creative ecosystem stepped in. In New York City, the Cultural Solidarity Fund (CSF) came forward to support individual artists and cultural workers with $500 unrestricted grants, redistributing over $1 million to 2,030 people over the course of three years.

The act of moving this amount of money alone is a feat to celebrate. In addition, the organizers of the Cultural Solidarity Fund accomplished this during a time of peak crisis and as a coalition of individuals and organizations, many of whom had no previous experience moving money nor working with each other.

The Cultural Solidarity Fund relied on organizers’ collective experiences as shepherds of solidarity in the arts and cultural ecosystem. Each organizer of the Cultural Solidarity Fund brought an awareness of the role they played in shaping an equitable cultural field, and used power analysis tools and community organizing experience to build infrastructure for a Money Moving Coalition. Whether as an individual member of a dance company or as the former lead of a state arts organization, every organizer of the Cultural Solidarity Fund knew what it was like to be in need of financial support, and committed to sustaining a movement for an equitable arts ecosystem. CSF’s organizers stood in equal strength, and built a responsive, equitable, and reproducible process for redistributing money.

Through this horizontal and formal group of organizations, individuals, and institutions, CSF organizers collaboratively raised and redistributed money to the more marginalized members of their communities: prioritizing Black, Indigenous, People of Color (BIPOC), immigrant, disabled, d/Deaf, and trans and gender-nonconforming artists, cultural workers, administrators, production staff, custodians, art educators, ushers, guards, and more who were most severely impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic.

The results?

- As of the publication of this report, 2,030 individual artists and cultural workers who otherwise did not have access to relief money received grants of $500 through the Cultural Solidarity Fund.

- Over 20 administrators and cultural workers who organized the Cultural Solidarity Fund translated their lived experiences into a model, the Money Moving Coalition, that can challenge economic inequity across times of crisis.

This report tells the story of why the Cultural Solidarity Fund came into existence, and how many people came together to raise and redistribute over $1 million in emergency relief grants at $500 each to over 2,000 artists and cultural workers in New York City. We hear from:

- CSF Organizers: Individuals who joined the Coalition and performed the day-to-day operations of the fund

- CSF Supporters: Individuals who supported and uplifted the Coalition without becoming organizing members

- CSF Grant Recipients: Individuals who received grants

- CSF Donors: Individuals and organizations who donated to the Coalition

- CSF Funders: Foundations who funded the Coalition

It includes analyses of the systemic factors specific to the cultural economy that work against or support Money Moving Coalitions through and beyond crises, including:

- How the COVID-19 pandemic presented a “political opening” that mobilized Cultural Solidarity Fund organizers to practice deeper solidarity with each other and the larger ecosystem;

- What enables people to participate in Coalitions and how we can sustain solidarity;

- How and why the organizers relied on relational organizing to fundraise for the Cultural Solidarity Fund;

- Why transparent, regular, and responsible reflection is crucial to both fostering and sustaining solidarity that moves beyond relief and towards recovery; and

- Why Coalitions bring us closer to materializing an equitable cultural economy.

As researchers, we expand these questions to outline recommendations for a cross-systems investment of resources into the Solidarity Economy, prioritizing the role of Money Moving Coalitions in supporting artists and cultural workers left out by the dominant extractive economy.

This report traces these results in three sections:

- A toolkit for moving money, including a series of worksheets and prompts to help organize Money Moving Coalitions

- A list of recommendations to sustain Money Moving Coalitions

- A history or case study contextualizing why the Cultural Solidarity Fund moved money the ways it did

Why haven’t the remaining 204 CSF grant applicants been funded?

The goal of this report is to resource more artists and cultural workers. It also is a tool for CSF organizers to use to reflect on the past four years’ work and imagine the next steps. Some of the money allocated for this grant has already been redistributed to Cultural Solidarity Fund applicants. Other money from this grant was redistributed to the organizers, who were otherwise not paid for their work developing this fund. To learn more about how we spent this grant money, write to culturalsolidarityfund@gmail.com.

As of the publication of this report, the Cultural Solidarity Fund is still fundraising to ensure they can process grants for the remaining 204 applicants, with 42% self-reporting an urgency level of four out of five, and all facing childcare, financial, food, housing, and/or medical insecurity. This report was written to raise the final $112,000, which includes grant and administration costs. You can contribute to meeting this goal at culturalsolidarityfund.org.

Once the Cultural Solidarity Fund reaches its goal of funding the remaining 204 applicants, it will sunset. But, the work of redistribution continues. The larger goal of this report is to make the work of CSF replicable and to compel you, Reader, in all your roles to shift our ecosystem from relief to recovery.

1 From The glorious pull of political openings by Lugay, M., 2023, Medium.

How to Organize a Money Moving Coalition

From Regranting to Redistribution: How CSF Moved Money & Why We Need Community-Centered Coalitions 07

Grounding Money Moving Coalitions in the Solidarity Economy

As Caroline Woolard and Nati Linares say in their 2021 report, "Solidarity Not Charity", “To survive and thrive, creative people are co-creating more humane and racially just economic models in their local communities.”1 The Cultural Solidarity Fund (CSF) is one model.

Like many other mid-pandemic relief efforts, the Cultural Solidarity Fund was planted intuitively against systems we know are working against us and with practices we know for their strength in resistance. The Cultural Solidarity Fund is a Money Moving Coalition that builds on centuries of organizing against a dominant economic system that further marginalizes the already oppressed — resistance for the abolition of slavery, for civil rights, for decolonization, for no more wars and for peace, for gender equity, for the right to marriage and the right to not come out, for #LandBack, for Black lives, for Another World. The Cultural Solidarity Fund’s commitment to moving money using the structure of a coalition is not new, but can be identified as part of the Solidarity Economy movement and Community Centric Fundraising. In each of these movements, we see culture bearers at the core resisting pain, exploitation, and extraction while building spaces for education, agitation, and organization.2

Resistance has always been sustained by cultural work, but cultural workers have not always been the focus of resistance movements. Without cultural struggles and ancestries, we would not have the voices nor platforms we have today.3 The Cultural Solidarity Fund, in the tradition of many past movements of the Solidarity Economy, puts these members of our community front and center.

Principles of the Solidarity Economy movement4

- Collective Care, Relationships, & Accountability

- Shared Resources & Shared Vision

- Liberation Culture

- Democracy & Process

- Education & Leadership Development

Guideposts for Community Centric Fundraising5

- Fundraising must be grounded in race, equity, and social justice.

- Individual organizational missions are not as important as the collective community.

- Nonprofits are generous with and mutually supportive of one another.

- All who engage in strengthening the community are equally valued, whether volunteer, staff, donor, or board member.

- Time is valued equally as money.

- We treat donors as partners, and this means that we are transparent, and occasionally have difficult conversations.

- We foster a sense of belonging, not othering.

- We promote the understanding that everyone (donors, staff, funders, board members, volunteers) personally benefits from engaging in the work of social justice—it’s not just charity and compassion.

- We seek the work of social justice as holistic and transformative, not transactional.

- We recognize that healing and liberation requires a commitment to economic justice.

The Cultural Solidarity Fund re-synthesizes these values on their website:

- Center trust

- Move out of the mindset of scarcity and competition

- Focus on solidarity as action, not as a symbol

- Expand the circle of care beyond our immediate communities

- Center the artist (the person) as the antidote to trickledown funding

- Require cooperation, collaboration, coalition, mutual accountability, personal reflection, and:

- Lighten the burden of the artists and cultural workers (people) requesting funds

- Prioritize those who have been historically excluded from funding

- Commit to transparency

- Believe that ALL artists and cultural workers in need deserve our support; our decision making process is not based on meritocracy

- Respond to the needs that arise throughout the process

Practices of a Money Moving Coalition

Coalitions like the Cultural Solidarity Fund (CSF) spring up organically from communities who recognize a need for redistribution instead of regranting. They are often urgency driven and more and more these movements are recognizing they are part of a larger Solidarity Economy Movement engaging Community Centric Fundraising. The practices below are drawn from interviews with and tools created by Cultural Solidarity Fund co-organizers and are designed to provide early organizers with shortcuts to mobilization.

NOTE: CSF examples were created in rapid response and should be seen as stepping stones, not the only way.

1. Understand your role and relationship to your ecosystem to identify the goal you want to work towards.

The work of Money Moving begins with knowing your role and relationship to your ecosystem, and identifying the goal you are working towards. For example, the Cultural Solidarity Fund grounded their goal in a place (New York City) and for a group of people (Black, Indigenous, People of Color (BIPOC), immigrant, disabled, d/Deaf, queer, trans and gender-nonconforming, and working class artists and cultural workers in New York City).

The Role & Relationship tool linked below has generative questions inspired by CSF organizers’ strategies. It will help you make informed decisions about where Money needs to be Moved, and by, with, and for whom. Use your answers to formulate your goal. For example, CSF’s goal was to raise funds for arts and culture workers facing housing, food, health and family care insecurity.

Tool: Roles and Relationships Worksheet

Tool: Roles and Relationships Worksheet

Tool: Defining Solidarity & Coalition Zine

Tool: Defining Solidarity & Coalition Zine

2. Find others who share your goal, and invite them to join you in coalition.

Based on your answers to the above questions, look to your local ecosystem. Who in your community and beyond might share your goal? You might look to organizations’ missions, individuals’ arts practices, and foundations’ giving histories to find people to organize with.

Organizers and organizations involved in CSF shared a goal but did not share the exact same lists of values. This wasn’t a breaking point! In fact, it’s one of the things that allowed CSF to grow and sustain, meeting more needs in the ecosystem. Coalitions don’t need to be fully aligned on values as long as they are fully aligned on goals. Part of the work of the coalition is bringing people into values alignment through work on a shared goal.

“Coalition work is not work done in your home. Coalition work has to be done in the streets. And it is some of the most dangerous work you can do.”

— Bernice Johnson Reagon6

3. Map your coalition’s access to resources.

Money Moving Coalitions have to fundraise to gather resources to redistribute. They don’t always start with a pool of money, but they are grounded in a deep understanding of who they want to move money towards because, by principle, they are led by the most marginalized and the least resourced.

Each collaborator in your coalition will have different access to the local ecosystem. For example, in the Cultural Solidarity Fund, IndieSpace, formerly Indie Theater Fund, had some connections with foundations and theater makers, while LEIMAY had connections with independent dancers.

Explicit power analyses will lead you to establish a grounding point of where you stand, your limitations, and where you want to end up. With the structure and space to focus, you can continually reiterate and shift your work from this grounding point. If power doesn’t transform at the paces of trust and need, on community terms, or sustainably, this is where you return to retrace your steps and try again.

Use this mapping activity to help you identify who you are connected to in the ecosystem, and who has access to what resources. Consider who has access to financial, people, time, and space resources:

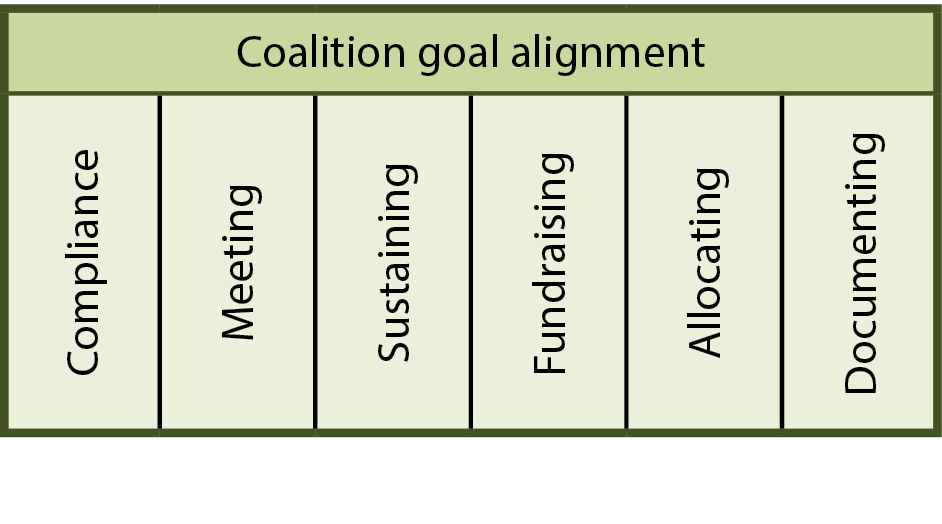

4. Iterate on infrastructure to raise and redistribute money.

Once you have a coalition and goal, you can begin the work of Moving Money. The tools below offer CSF’s way to build this infrastructure for Moving Money, but it may not be the one your Coalition ultimately needs and uses. Iterate on this infrastructure by using the previous mapping activity and developing tasks, roles, and responsibilities for each co-organizer in the Money Moving Coalition.

Compliance

Pick a fiscal sponsor from within the Coalition who will hold the raised money before it is redistributed. The fiscal sponsor will need to be prepared to:

- Oversee accounts

- Manage receiving money, including banking and other organizational information necessary to receive funds from donors

- Manage payments, including payouts of grants to applicants, to staff, and for infrastructural investments like the fiscal sponsor and payments for subscriptions

- Provide overview of cash flow

- Report back on money

- Shareback any necessary paperwork for donors, including acknowledgement letters of contributions and grant reports

- Collect any necessary paperwork and information from recipients, including addresses7

- Have tax reporting infrastructure ready and file taxes

Example: CSF and IndieSpace MOU agreement

Example: CSF and IndieSpace MOU agreement

Meeting

Develop a pace for meeting and collaboration.

- Set a regular meeting time that meets all participants’ needs for flexibility and stability. Change the meeting time when needed.

- Assign tasks and roles for regular meetings, including note-taking, scheduling, and sending follow-ups.

- Use democratic decision making processes.

Sustaining

Create administrative structures that sustain individual organizers’ lives and the Coalition’s work.

- When possible, raise money to compensate administrative labor on par with leadership, and in addition to redistributing money.

- Ask organizations to compensate their staff’s time spent working on Coalition efforts as an in-kind donation. Many organizations also reserve a set number of work hours every year for volunteer time.

- Share labor by inviting organizers to be in relationship with the Coalition in a variety of ways in the forms of labor, money, relationships, resources, advice, and more.

- Include time for individual and collective reflection.

Fundraising

Raise the money.

- Collectively decide how to manage new relationships and sustain existing relationships with donors.

- Use existing relationships with other funders and orgs to spread the word to raise money

- Use existing relationships with other shared spaces to spread the word to raise money

- Identify coalition members interested in collaboratively writing grants to raise money, including from partner organizations.

- Create and use social media to spread the word to raise money.

- Create a social media toolkit so member organizations and others can do the same

Example: CSF thank you letter to a foundation

Example: CSF thank you letter to a foundation

Example: CSF's Social Media Kit

Example: CSF's Social Media Kit

Example: CSF’s Classy platform

Example: CSF’s Classy platform

Allocating

Move the money.

- Choose a grant amount that meets recipient and organizer needs. For example, CSF chose $500 grants to meet the needs of undocumented artists and cultural workers, and lessen the administrative burden for the financial sponsor.

- Prioritize relationship building on the terms of the community to know how communities will receive and respond to the application.

- Develop a trust-based application to meet your communities’ needs

- Prioritize accessibility needs of your applicants’ community, including for those who are vision, hearing, and mobility disabled.

- Translate the application into languages spoken in your community. Compensate translators from your community for these translations. Avoid using Google Translate.

- Remove any elements that could be onerous, such as an application fee.

- Develop an application review process that prioritizes the communities the Coalition wants to redistribute to.

- Be transparent with your lottery process by recording it and live streaming it on your social media.

Example: One of CSF's lotteries for grantees showing the use of RandomPicker

Example: One of CSF's lotteries for grantees showing the use of RandomPicker

Example: CSF's Applicant Vetting Process

Example: CSF's Applicant Vetting Process

Documenting

Contribute to a movement against extraction by showing how you model an alternate way of survival and thrival.

- Make regular time to document your Coalition’s work. Consider including meeting notes, press coverage, funder and grantee testimonials, survey responses, and organizer introspection. Store this information somewhere that is accessible to all Coalition members.

- Use surveys to gather testimonials from grantees, donors, and organizers.

- Regularly share updates with your community. Include how much money has been moved, from and for whom, and testimonials.

- Create social media toolkits to encourage others to share these updates widely, and reflect on their own experiences.

Example: Testimonial from a CSF Organizer

Example: Testimonial from a CSF Organizer

5. See The Money in the World

Money supports individual artists and cultural workers and signifies an investment in members of our community who otherwise see little infrastructural care. The impact of centuries of undervaluing artists and workers is still present: CSF grant recipients spoke repeatedly about their worries that receiving the money for themselves meant denying other artists and cultural workers this support.

Seeing money spread equitably through our communities causes individuals to rethink their scarcity mindset, and to understand the power of helping to move that money. The power of donations is always best spoken to by grant recipients. The artists and cultural workers who received the CSF grants share:

“[The $500] was a relief first because it finally came through, and second, because it covered an unexpected expense. And that’s the stuff that we panic about as artists.”

—Anonymous, CSF Grant Recipient

How can I participate without being a member of a Money Moving Coalition?

At any point, you may recognize that this work isn’t feasible for you at this moment — that’s okay. One value of solidarity-based Coalitions is inviting and supporting organizers to step back when needed. The work of Money Moving is not limited to a coalition. Here are three different roles you can take on to support this work:

Supporting Strategy

- Model and promote the values of Money Moving Coalitions and contextualize the larger movements they sit within.

- Exchange knowledge between Money Moving Coalitions. Give advice based on knowing your local ecosystem, and hear advice based on how others respond to their ecosystems.

- Use the learnings of the Coalition to shape your own work outside of Moving Money.

- Communicate externally about what Coalitions can do and why you support them.

- Speak up when Money isn’t Moving in transformative, just, or equitable ways.

Fundraising & Funding

- Give money from your organization or as an individual.

- Do a power analysis on your organization or community to see what resources you can move. Then, move these resources.

- Encourage other institutions, foundations, organizations, and individuals to join and/or contribute resources to the Coalition.

- Solicit money from individuals and organizations in your community.

- Use existing relationships with funders to ask for resources to be directed towards Coalitions and other Money Moving efforts

- Promote the work of the Coalition in as many spaces as possible, including meetings and social media.

Shepherding the Money into our Ecosystem

- If you receive money, know your power in modeling an investment in culture and use the money to get closer to thrival.8

How to Sustain Redistribution

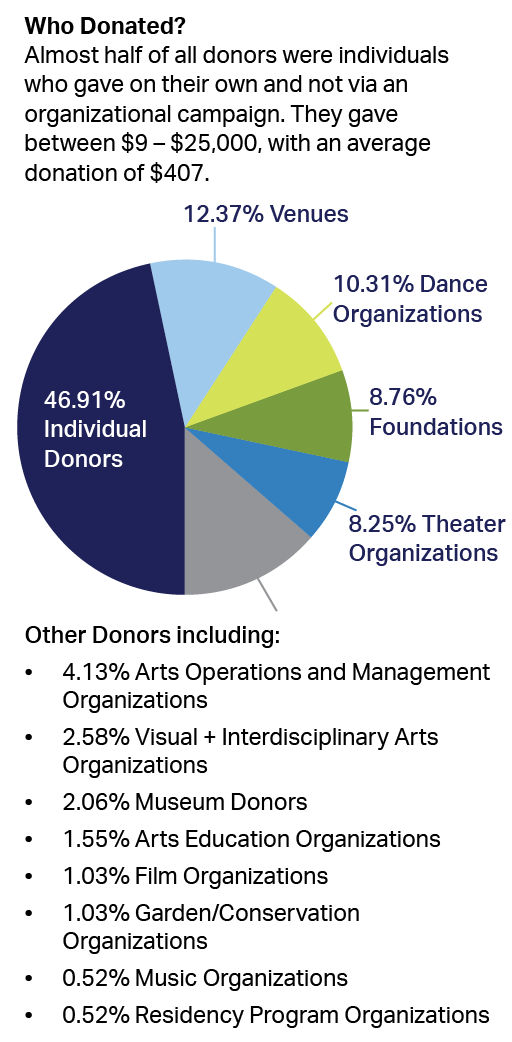

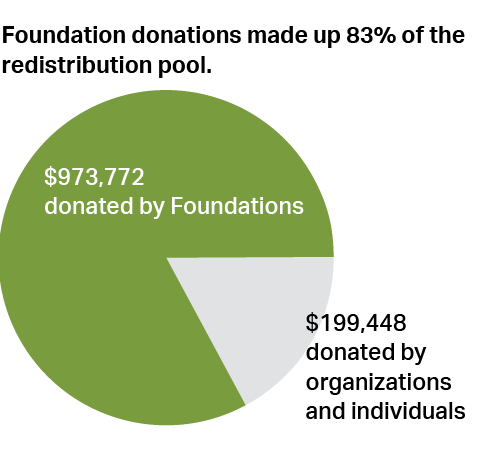

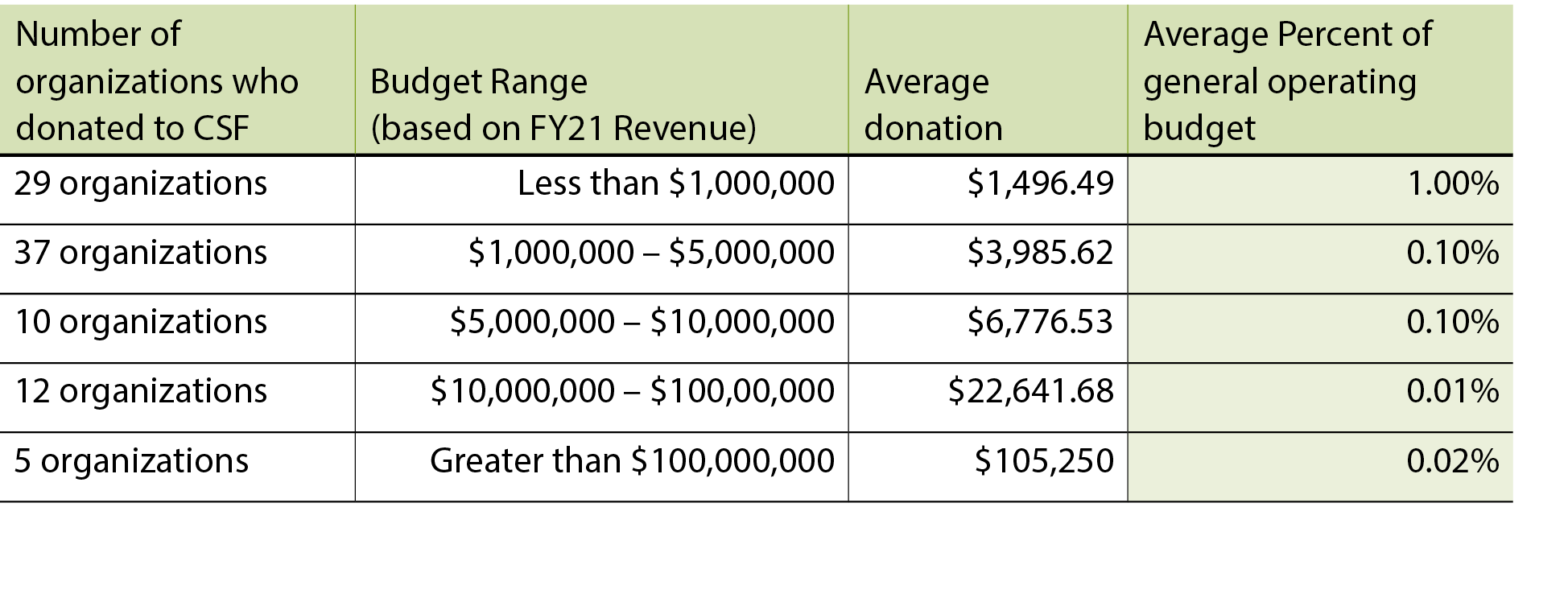

In order for us to all step into Money Moving, there must be an initial re-seeding of solidarity from those with the most resources. Though everyone can do the work of redistribution, philanthropy must do the largest part. Foundations were a significant force in shaping the trajectory of the Cultural Solidarity Fund (CSF), contributing 83% of CSF’s budget. Cultures of giving dictate the past, present, and future of redistribution.

We make these recommendations knowing that each of us has the ability to take on the roles of organizer, ally, donor, and artist or cultural worker. These recommendations are heavily guided by other organizers’ work on shifting economic paradigms — this call for redistribution is not new.

Recommendations

- Follow the lead of the most marginalized and explicitly center Black, Indigenous, People of Color (BIPOC), immigrant, disabled, d/Deaf, queer, trans and gender-nonconforming, and working class artists and cultural workers.

- Raise both individual and collective understanding of class privilege. When we understand our role in our ecosystem, we can shift dynamics and redistribute power.

- Overcome the scarcity mindset to shift the economic paradigm. Recognize that there are more resources that we can all collectively access, and that one person accessing a resource should not prevent another.

- Invest in Solidarity Economy infrastructures, including the Money Moving Coalition Model, that allow more people to resist exploitation and build alternative systems to challenge the nonprofit industrial complex, Racial Capitalism, and the dominant extractive cultural economy.

- Use trust-based funding principles to resource and build relationships with the organizations led by, with, and for the most marginalized.

- Shift from regranting to redistributing by inviting communities to collectively control how funds flow across the ecosystem.

- Work towards and sustain a safety net, including by using the language of the Solidarity Economy movement.9 Invest in infrastructures that seed solidarity, and hold the movement accountable to this change.

Follow the lead of the most marginalized

Everyone can participate in redistribution work, but it must be led by, with, and for the most marginalized.

Within the U.S., this means pushing against Racial Capitalism and Settler Colonialism by prioritizing the needs and leadership of Black, Indigenous, People of Color (BIPOC), immigrant, disabled, d/Deaf, queer, trans and gender-nonconforming, and working class community members. In the art world, these marginalizations show up in different ways.10 There are numerous medium-specific efforts that you can look to,11 but ultimately, this wisdom comes from deep relationship with community members.

When we build towards a goal with and for Black, Indigenous, People of Color (BIPOC), immigrant, disabled, d/Deaf, queer, trans and gender-nonconforming, and working class community members, we don’t lose anyone on the way to activating that goal.

Caroline Woolard and Nati Linares, in their 2021 report "Solidarity not Charity,"12 call for all members of our cultural ecosystem to shift resources and attitudes, language, and beliefs related to benevolence, charity, and perceived expertise by:

- Embracing systems-change;

- Learning about, acknowledging, and repairing histories of harm caused by their institutions; and

- Identifying and shifting how people in the sector show up in spaces.

This report lays out many strategies for philanthropists to reckon with their identities and identify the most marginalized members of their communities.13 Some of these strategies are:

- Get data about inequities in the allocation of funding in your region along racial and cultural lines. Measure your organization’s prior investment in Black, Indigenous, People of Color (BIPOC) staff and grantees: culture-bearers and culturally-grounded organizations. Set internal and external benchmarks and practices for repair.

- Conduct a power analysis.

- Do diversity, equity, and inclusion training that is led by artists and culture-bearers.

- Engage in somatic and embodied leadership training that addresses social position, rank, trauma, and race.

Raise both individual and collective understandings of class privilege

We must all internally reckon with historic access to resources. Ultimately, this should lead to ceding and redistributing resources.

“Class privilege is a way to describe one’s access to resources, power, and opportunities within a system and culture that systemically advantages the mostly White, ruling class.”

— Resource Generation14

Understanding what marginalization looks like in different contexts requires understanding how class dictates access. When we all understand our roles in the economy, we can more strategically redistribute power from those with abundance to those without.

People must advocate for equitable redistribution of resources together and across lines of class. Those with wealth should contend with how much they have compared to others, and commit to redirecting resources more equitably to the working class and poor.

Below we share resources for individuals, organizations, and philanthropic institutions to help contend with personal and institutional privileges.

One helpful guide to understanding what resources you as an individual have access to is Resource Generation. Their Redistribution Guidelines15 suggest that people in the top richest 10% of net wealth16 in their generation:

- Return the wealth by redistributing all inherited wealth and/or excess income.

- Escalate redistribution and turn up the heat on giving.

- Begin to spend down, and spend into movements.

- Say “No!” to making wealth off of wealth by giving capital gains to social justice movements.

- Give between 1% and 7% of your assets annually.

A helpful resource for organizations is Working Artists and the Greater Economy (W.A.G.E.), which has a digital calculator for institutions to know what fair pay means at their economic scale.17 Only 27 out of hundreds of community-based arts organizations in New York City are W.A.G.E. Certified.18 None of the 34 Cultural Institution Group members, who collectively represent the largest and oldest organizations in the city’s arts and culture ecosystem, are W.A.G.E. certified.19

W.A.G.E. identifies a compensation floor for different professional fees, and scales those fees based on organizations’ total annual operating expenses. Simply put: “the higher an institution’s annual operating expenses, the higher the fee.”20

Another resource comes from Cultural Solidarity Fund co-organizer Michelle Amador, who offers these steps to dismantling institutional Racial Capitalism in organizations:

- Invest in education that helps staff understand their organization’s place in the larger arts and culture economy; and

- Transparently share where organization resources go (and don’t) within the organization and outside.

For some individuals and organizations, and for all philanthropic institutions, this means ceding resources. For many more it means creating a culture where redistribution is affirmed and valued. We see an investment in political education as necessary to build this culture. Anti-Capitalism for Artists is another resource that offers this.

Until we incorporate an understanding of class politics, we cannot turn a struggle against racism, sexism, ableism, etc. into equality.21 By knowing our relationships to the production and distribution of resources and encouraging others to do the same, we can better comprehend our role in bringing change. Our path is to not develop a new analysis of class, but to rediscover it and share it to inspire future generations to mobilize.22

Overcome the scarcity mindset

Class analysis helps us understand that there are more resources that we can all collectively access. Today, instead of a shortage of resources, we see a monopolization and hoarding of resources. When we contend with what we need and accordingly cede or receive resources, we will shift our relationship with money, and overcome the scarcity mindset. When we have both internal and field-wide contention with the false narratives of eternal shortage, we will see more resources in and across our field.

“What can we do on an ongoing basis, in the absence of a safety net provided by the federal government? What can we do with billions of dollars in endowments? With the community reach and breadth that service organizations can provide? If we just work together and get out of our own way and stop only prioritizing our own organization’s survival, but look to each other for collective survival...”

— Randi Berry, CSF Organizer & Executive Director, IndieSpace

Overcoming the scarcity mindset is cemented with actions. Without action and with performative solidarity, we uphold the scarcity mindset. Operating against a scarcity mindset means committing to and seeing abundance23 in the arts, and committing to ‘and’, not ‘or’. That means more money for larger organizations and smaller organizations, more money for organizations and artists, more money for artists and cultural workers, and more money for those most marginalized by our current systems.

“Funding shouldn’t be taken away to give to someone else. More funding should be given to more people.”

— Laurie Berg, CSF Organizer

One existing strategy to see abundance could be in percentage for arts campaigns. A few research participants proposed asking for more than 1% of the New York City budget to be dedicated to arts and cultural funding. This shifted their mindset to imagine the right to abundant funding for arts and culture. These research participants acknowledged that there is enough money in the world for us all, and that uniting to advocate for it strengthens the possibility of thriving. Why not ask for more than 1% for the arts?

Overcoming the scarcity mindset requires that those with access to wealth put money, resources,and time behind statements of solidarity. A few research participants mentioned feeling wary when they hear organizations speak to Diversity Equity Inclusion Access (DEIA) efforts, decolonization, mutual aid, and Black Lives Matter. Especially since the pandemic, well-endowed individuals and organizations have expressed verbal commitments without changing their actions.24

“Maybe you’re co-opting the work of our organizations right? By plastering [it] on this wall... My question behind it is, so what now? Because for many folks coming through, it’s going to look like a major accomplishment, a major recognition of our voices in an institution that historically has never been welcoming of us... Others are seeing this as ‘How progressive, how inclusive, how diverse!’ But it’s still an institution that is very racist in its practices and that’s not being addressed.”

— Anonymous, CSF Organizer

To embody solidarity and overcome the scarcity mindset:

- Resource small organizations and individual cultural workers at the same pace, rate, and length as larger organizations and individual artists, respectively.25

- Fund life, not just livelihoods.

- Study the legal, administrative, and personnel structures of small organizations and individual community members at the same depth as larger organizations.

- Analyze access to wealth, using tools like W.A.G.E., Anti-capitalism for Artists, and Resource Generation, and accordingly shift resources to those experiencing precarity.

Invest in infrastructures that allow people to practice solidarity

Investing in existing Solidarity Economy practices enriches the soil of our ecosystem. The Solidarity Economy Movement prioritizes resourcing people to survive and resist, while enabling them to build the structures that help them thrive.

Money Moving Coalitions are one Solidarity Economy model that both undoes the dominant extractive economy and manifests a new one by overcoming competitions of scale enforced by the scarcity mindset. Resourcing the Money Moving Coalition model incentivizes organizations to prioritize supporting underresourced individuals while sustaining infrastructural investments.

“I’m not gonna say all institutions are evil, [because] they’re also [serving] communities. The issue is when we start sacrificing the actual community [to be able to] maintain the institutional structure.”

— Ximena Garnica, CSF Organizer & LEIMAY Artistic Co Director

The Money Moving Coalition model puts people at the center of transformation. Solidarity requires that our ecosystem looks at workers, community members, and leaders as equally responsible for Just Transition. The Climate Justice Alliance defines Just Transition as “a vision-led, unifying and place-based set of principles, processes, and practices that build economic and political power to shift from an extractive economy to a regenerative economy. This means approaching production and consumption cycles holistically and waste-free.”26 We must learn from these groups to build the ecosystem we deserve.

“As a contributor to and beneficiary of White supremacy and the extractive economic system, philanthropy has a moral obligation to not only abundantly resource the Black, Indigenous, People of Color (BIPOC)-led community organizing work... It must also resource groups like the U.S. Federation of Worker Cooperatives and New Economy Coalition to support our movements in re-imagining how to build and participate in new forms of economy.”

— Justice Funders27

Additional Solidarity Economy organizing models to invest in and resource include:28

- Land and Housing: Community Land Trusts, Cooperative Housing, Housing Cooperatives, Cooperative Co-working Spaces, Cooperative Venues, Cooperative Stores & Galleries, Cooperative Studios, Cooperative Recording Spaces, Cooperative Darkrooms, Cohousing and Intentional Communities, Cooperative Co-working Spaces, Retreats, Residencies, or Landback Networks

- Labor: Worker Cooperatives, Multi-stakeholder Cooperatives, Producer Cooperatives, Time Banking, Mutual Aid, Barter Systems and Non-Monetary Exchange.

- Money and Finance: Participatory Budgeting, Credit Unions, Community currencies, Community Development Financial Institutions (CDFIs), Community Loan Fund, Solidarity Philanthropy and Grantmaking, Democratic Loan Funds and Grants, Cooperative Billing and Accounting, Cooperative Insurance, Cooperative Marketing, Patronage Cooperatives, Unions and Guilds, Universal or Guaranteed Basic Income (UBI/GI).

- Energy and Utilities: Community Solar, Community Broadband, Energy Democracy

- Food and Farming: Community Gardens, Community Supported Agriculture, Food and Farm Cooperatives, Community Fridges

- Media & Technology: Worker-Owned News Media, Community Radios, Platform Cooperatives, Solutions Journalism, Open Source, Copyleft, Cooperative and Collective Study Groups.

Use Trust-Based Funding principles

The most sustainable way to resource these Solidarity Economy models is to share power by using Trust-Based Funding principles.29 These principles encourage funders to connect deeply with organizations led by, with, and for Black, Indigenous, People of Color (BIPOC), immigrant, disabled, d/Deaf, queer, trans and gender-nonconforming, and working class community members.

Unfortunately, as philanthropy currently functions, the most marginalized are explicitly not centered. Of philanthropic foundations in the U.S., 92% are led by White presidents and have a staff body that is 83% White. Less than 7% of total grantmaking is designated to support communities of color.30

Because of how Whiteness functions in philanthropy, fighting for trust in philanthropy will be difficult. The Kindle Project31 lays out some challenges:

- For donors and foundations, challenges can range from internal reckoning with access to power to shifting existing financial structures to meet community needs.

- For community-based decision makers, the challenges can be similar, but are complicated by shifting internal community dynamics when relationships to power change.

Still, the Kindle Project proposes that we can push through these challenges when we learn to prioritize relationships.

One exciting example is the work of the Whitman Institute and their collaborative project, the Trust Based Principles Project. The Whitman Institute, their grantee partners, and other funder allies developed the following six principles, by reflecting on and centering their relationships with each other. These principles align with the call for Just Transition in philanthropy.

The Trust-Based Philanthropy Project32 principles and practices are:

Provide Multi-Year, Unrestricted Funding: Give grants that last longer than one year and can be used by grantees as needed. CSF donations were re-allocated from multi-year unrestricted grants given to organizations to meet community needs in a time of sudden crisis. With more multi-year unrestricted grants, more organizations would have been able to give.

Do the Homework: Make an effort to get to know your grantees personally and refrain from asking them to pitch themselves. CSF organizations and organizers took the time to communicate goals to their communities, rather than relying exclusively on CSF Organizers to tell the story. With foundations, too, taking on this labor, CSF organizers may have been less burnt out.

Simplify & Streamline Paperwork: Remove redundant asks from applications. To support CSF, Mellon made an active choice to help organizers document and share their work, so that the Fund spent less of its time on paperwork, and more on redistribution. With more foundations using this practice, the Cultural Solidarity Fund could have prioritized documentation that serves its communities’ goals, rather than those of the foundation.

Be Transparent & Responsive: Share explicit details about what you can and cannot fund, whenever that changes. Donors to CSF who had restricted grant funds shared their limitations and worked with CSF organizers to still redistribute what they could. With further transparency, more workarounds to fund limitations could have been co-developed, and more money could have been redistributed.

Solicit & Act on Feedback: Actively seek grantees’ input, and shift practices to meet grantees’ needs. For CSF, Mellon made an active choice to meet organizers’ need for a verbal report-back, and have adapted this for other grant reporting processes. Many donors have not asked for feedback on their grantmaking processes, and thus, leave their future grantmaking programs to be less inclusive.

Offer Support Beyond the Check: Shift power through and beyond the redistribution of funds. Donors to CSF with connections to foundations shared their relationships with organizers, raising more money. With a clearer power analysis, all members of our cultural ecosystem can feel equipped to redistribute.

The Whitman Institute followed these principles to spend out their assets by 2022. Across two decades, they provided unrestricted, multi-year funding to 170 grantees.33

Shift from regranting to redistributing money

In this report, we define redistribution as autonomous community control of funds, and monies are moved based on reflective, responsive, reciprocal relationships of interdependence between human communities and the living world upon which we depend. Justice Funders calls this Regenerative Grantmaking.34 We define regranting35 as efforts that move money to those who have the infrastructure to redistribute that money.

We recognize that regranting is a successful strategy. It is what allowed the Cultural Solidarity Fund to move money. But, as the Movement Strategy Center36 lays out, regranting is not perfect. It can limit the scale and scope of money-moving efforts through bureaucracy and by creating further alienation between donors and grantees. For example, funders were not able to build and sustain relationships with individual artists and cultural workers through the Cultural Solidarity Fund. Is this one of the reasons why donations have slowed? When funders rely on researchers and organizations to keep them in touch with individual artists and cultural workers, details can be left out and empathetic understanding can be compromised.

“Those who hold the purse of relief can’t be disconnected from the pain.” 37

— Yancey Consulting Group, We Are Bound

To fully transform from regranting to redistribution, grantmaking must be democratized by allowing money to move with co-accountability, rather than top-down bureaucracy. This means inviting the people you fund to not just control what resources they receive, but to collectively decide how funds flow across the ecosystem.

Redistribution focuses on using existing infrastructure and building new infrastructure to see a collaborative commitment to moving money. Rather than resources moving based on one organization’s capacity, redistribution relies on many organizations, people, and institutions working collectively.38 Justice Funders uses a spectrum from extractive to regenerative grantmaking (see diagram above).

To shift from regranting to redistribution, all foundations and large organizations should actively build relationships with the most marginalized and ensure communities collectively control the flow of resources.39 When there are more voices helping shape the flow of resources, we are better suited to meet everyone’s needs.

Participatory grantmaking, grassroots grantmaking, and mutual aid are all practices within the Solidarity Economy40 that support Just Transition. These shifts in sharing resources “disrupt the existing ‘winner takes all’ approach”41 which is inherently unfavorable to Black, Indigenous, People of Color (BIPOC), immigrant, disabled, d/Deaf, queer, trans and gender-nonconforming, and working class people.

A Money-Moving Coalition is another model that democratizes grantmaking42 and prioritizes collective control of resources. This model can facilitate redistribution by sharing labor based on capacity and expertise across a coalition structure. For example, the Cultural Solidarity Fund saw IndieSpace, formerly Indie Theater Fund, take on the labor of moving money to applicants, while individual organizers used their experiences fundraising to liaise with foundations and donors.

Collective participation in redistribution decreases competition over resources and increases collaboration towards meeting communities’ needs. When we collectively participate in redistribution, we transform the system by prioritizing giving more resources to those historically marginalized while building an equitable economy.

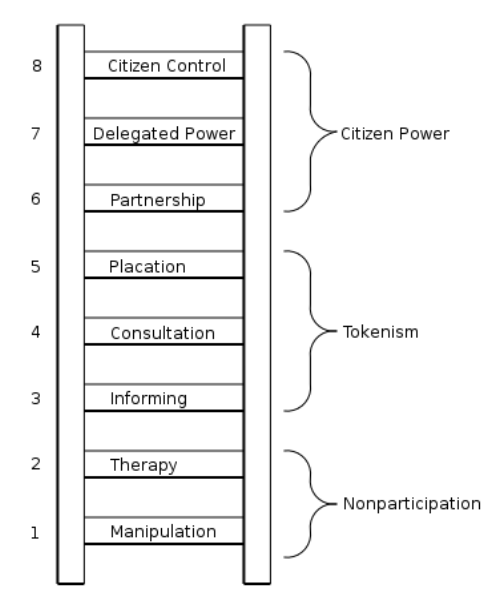

Sherry Armstein “A Ladder of Citizen Participation” offers a diagram of resident participation (see diagram on left) to understand the different ways funders engage communities, culminating in true transformation from extraction to solidarity. Let’s use it to look at the funding of the Cultural Solidarity Fund:

- We saw most donors start their engagement with Money Moving through therapy. These funders made one-time donations, but did not develop long term plans to sustain CSF. For example, most funds from foundations were limited to a one-year grant period.

- This report is an example of consultation. The Mellon Foundation is asking CSF (and others in the field) for input on funding strategies that meet needs beyond crises. However, CSF organizers can never be sure that Mellon will implement their strategies or follow their recommendations. In this case, power remains with the foundation.

- A potential future goal might be to get all donors and recipients to steward the Cultural Solidarity Fund into a sustained state of resident power. One way to get there is for all philanthropists to move from consultation to partnership, by joining the Money Moving Coalition officially and sustaining relationships with the Cultural Solidarity Fund, its organizers, its supporters, and its recipients. This would look like becoming a part of CSF by committing time, labor, and resources.

Ultimately, the best tool for this shift is relationship building and collaboration.

“Share power and support: If you share power, people will step up. If you don’t also share support, they will fall down.

Combine technical and community expertise: Don’t ask people to decide without technical expertise.

Institutionalize participation: Make it part of official decision-making processes, not a one-off event or special funding stream.

Meet people where they are: Rather than asking people to come to your spaces, engage them in their existing community spaces.

Step back as decision-makers, and step up as conveners, advisors, and facilitators.

Abandon elite rule, and let the people decide. Give democracy a try.”

— Josh Lerner 43

Build a Safety Net for artists & cultural workers

Ultimately, the tools and resources above lead us through world building to an ecosystem that guarantees safety nets for all who sustain creativity, life, and humanity. When we behave like we value each other, we create a world where we do.

“World-building creates opportunities for people to practice better ways of living, working, and meeting their spiritual, social, and material needs today. These experiments—whether mutual aid groups, cooperative businesses, democratically run investment funds, land trusts, alternative currencies, publicly owned utilities, open technology platforms, restorative justice communities, or sites of cultural production—build community, transform people’s perceptions and capacities, and create possibilities for larger-scale changes down the line.

Even when such experiments are small or hyperlocal, they offer the “threat of a good example” by demonstrating that another world is indeed possible.”

— Alexis Frasz 44

Money Moving Coalitions like the Cultural Solidarity Fund are one threat of a good example. To bring forth the arts and culture worlds we deserve, we must build an inclusive safety net composed of many different Solidarity Economy models and practices.

One CSF organizer talked about the Comprehensive Employment and Training Act (CETA) program as one model for this safety net. In the 1970s, CETA provided 20,000 artists and cultural workers across the country with full-time employment.45 In New York City, CETA funding employed 600 artists through five nonprofits starting in 1977. Unfortunately, despite its success, CETA closed in September 1980 due to federal funding cuts.46

What could have happened if CETA continued, or a similar state support program was designed? Perhaps the work of all the COVID-19 relief funds would be less necessary, more manageable, and more sustainable.

“If government funding of the arts [via CETA] had been maintained instead of going into the private sector, the Job Development program would have had an easier time placing people in permanent jobs…”

— Joan Snitzer 47CCF Job Development Program Counseling Coordinator

Structures of the U.S. art economy and larger state structures slow and prevent the creation of safety nets for artists and cultural workers. Artists Relief, a national grantmaking fund, had to dissect Internal Revenue Service (IRS) law48 in order to understand its ability to redistribute. The organizers of Artists Relief realized their redistribution was limited by how the federal government defined crisis.49

In times of crisis, state support allows us to see possibilities only for relief. For true recovery, we need the state to move beyond crisis-limited or short-term investments in redistribution towards a structure that makes resources available to all. We must imagine what it could look like if the U.S. maintained state infrastructures that enabled more people to survive and thrive, like other countries.50

“When you look at the countries that are giving away, based on taxation or philanthropy, we’re giving away the least with our 5%. Many countries mandate 20% or more.”

— Caroline Woolard, CSF Supporter

In New York City, the call to build a safety net for arts and culture goes first to the Department of Cultural Affairs (DCLA) to:

- Dedicate more of the city budget to arts and culture, with a focus on funding organizations in the Community Development Fund which represents all but 34 cultural organizations across New York City.

- Partner with private funders to map out and fill gaps in resourcing.

- Fund coalition-based work and give money to participants in intersectional and cross-sectoral collaborations.

- Provide additional resources for small and large organizations to build collaborative infrastructures for moving money, including legal and infrastructural support. Incentivize grantees to do the same, and fund them when they share non-monetary resources.

- Provide portable benefits for independent artists and cultural workers.

- Commit to resourcing communities by funding efforts across scale, including through support for and of Money Moving Coalitions, Universal Basic Income experiments, a New York City artist and cultural worker census, and Solidarity Economy efforts, to get us to a safety net.

Beyond New York City, the call to safety net builders is similar:

- Invest in and incentivize coalitional collaborations, following the recommendations above.

- Prioritize, incentivize, and resource communication between regional safety nets to build a national safety net that meets specific needs while remaining flexible.

While Money Moving Coalitions like the Cultural Solidarity Fund have provided some security to our arts and culture ecosystem, they cannot build a safety net alone. Neither can the 500+ organizations, efforts, campaigns, and movements that our research participants named as stewards of Solidarity and Coalition (see Appendices: Parallel Efforts). For any true transformation of our arts and culture worlds, we need full ecosystemic support — from organizations to each other and to individuals, in and across sectors.

The work begins with financial investments from those with money to those who can move money directly to communities. It continues with members of the arts and culture ecosystem participating in exchange and reciprocal practices with non-monetary resources to meet each others’ needs.

For relief to become recovery, there must be an overarching body to infrastructurally support this work. While the state can be theoretically positioned at the necessary scale to do this, it isn’t yet. In the meantime, while pushing for this change, organizations and individuals will continue to step in to provide a safety net as best as they can. The work will only end when there is an intersectional and institutional commitment to providing abundant resources to all communities.

Case Study: The Cultural Solidarity Fund

Re-Seeding with Solidarity

Inspired by writing by Michelle Amador, Cultural Solidarity Fund (CSF) Organizer.

"Can we be like mycelium? Can we be like soil?

What might we re-compose

with the nutrients being released into the system right now?

What if this moment, painful and raw though it be (and grief has its place),

is not just the ending of a world

but the beginning of something new?”

— Annalisa Dias, Decomposition instead of collapse: Dear theatre, be like soil

Nature is full of reciprocal relationships that build the biodiversity essential to all health and wellbeing. As we consider the health and vibrancy of our arts ecosystem, how will we transform our relationship to solidarity, and solidarity itself? How will we ensure that we are not just watering the big lawns, or favoring the big trees, but are collectively supporting all plants that grow? How do we ensure that various arts and culture forms do not go extinct due to lack of resources?

To answer these questions and do the work of re-seeding with solidarity, we must return to ancestral practices and the practices of the Solidarity Economy. Our arts and culture “parks”, once filled with regenerated soil, can allow not only play, picnic, and respite, but also collaboration, redistribution, and justice.

This next portion of the report focuses on the role of the Cultural Solidarity Fund in regenerating the soil and solidarity of New York City’s arts and culture ecosystem. This work of regenerating soil cannot be done by one organization alone. In this park, the Cultural Solidarity Fund is but a single fava bean plant or a shrub of comfrey. It will take many more coalitions like CSF and other models that look different to fully regenerate and sustain New York City’s arts and culture ecosystem. We write this report hoping it can be one piece that helps regenerate the soil by enabling each of us to realize our potential as gardeners.

Solidarity, like healthy soil, has many facets, and no single entity can offer all solidarities.51 The Cultural Solidarity Fund is one form of solidarity with a focused goal. This Money Moving Coalition helped redistribute money to artists and cultural workers including individual artists, administrators, production staff, custodians, art educators, ushers, guards, and more. It prioritized Black, Indigenous, People of Color (BIPOC), immigrant, disabled, d/Deaf, and trans and gender-nonconforming individuals who have been most severely impacted by the pandemic. Our research participants said that CSF regenerated the arts and culture world by:

- Moving as much money to as many community members as it could;

- Listening to each other as co-organizers and helping each other grow;

- Bringing different people together regularly to engage in democratic decision-making towards one shared goal;

- Acknowledging that someone affirming their need was enough for others to meet that need;

- Thinking about who wasn’t in the room that was Moving Money; and

- Committing to funding everyone who applied to receive money.

Timeline

The Cultural Solidarity Fund brought together over 250 organizations and individuals from across New York’s creative sector to move over $1,000,000 to fund over 2,000 artists and cultural workers with grants of $500 each.

The system was built against and without us.52We find ways to push against it, and to build a new world.53

March 11, 2020 COVID-19 lays stark inequities bare

In 2020, the world’s social and economic systems fall into a deeper state of collapse, revealing the already stark inequities in our society. On March 11, COVID-19 is declared a global pandemic by the World Health Organization. By March 9, most of the world, including New York City begins to shut down.

In the art world, this looks like canceled gigs, slowing pay, and unsold work, on top of profound loss and grief. It is a continuation and worsening of devaluing artists and cultural workers — the very people who the global population was turning to in their times of isolation, loss, and grief for comfort.54

“When the COVID-19 pandemic hit NYC, 66% of arts workers lost their only source of income. Like many creative fields, they had little to no reserves to support them during a crisis, revealing the lack of any financial safety net comparable to those afforded to people in other professions.”

— Cultural Solidarity Fund

Spring 2020 Acting on a political opening to redistribute resources

On May 25, 2020, George Floyd is murdered by Minnesota police officers, and the world, again, fights for justice against anti-Black police brutality and racism. Amidst the pandemic, protests spread across the country and call in local organizers to manifest the change they demanded. We cannot just ask for a world with no police; we must model community control and self determination.

For some, acting on this political opening looks like hosting art builds for protests, while for others it looks like neighborhood mutual aid. The arts and culture world, too, sees concurrently emerging movements to support the community and reach more people.

- In New York City, the Cultural Institutions Group spreads information to over 300 non-profits, via Culture@3PM55

- Funding efforts like Artists Relief distribute money to 4,000 artists nationally, in $5,000 emergency grants56

Summer 2020 It’s not enough, especially for individual artists

Nine months after the pandemic began, we see so many relief efforts — but, their scale and reach isn’t enough. Many individual artists and cultural workers, especially those on the margins, remain under-supported.

Fall 2020 “How can we be in deeper solidarity?”

Ximena Garnica is an artist and the leader of a non-profit arts organization and attends Culture@3PM meetings.

In October, Ximena speaks up in a Culture@3PM meeting, naming that the space is in solidarity with organizations like hers by sharing critical information at a time of crisis. However, she calls out the symbolic solidarity taking place in the calls and voices the need for Culture@3PM to directly redistribute cash and support to individuals in the ecosystem.

At first there is no response. But when another artist and leader of Caribbean Cultural Center African Diaspora Institute, Melody Capote, stands up and encourages this additional act of solidarity, the leaders of Culture@3 are moved to create a working group.

The first participants meet in November 2020, but some of them are confused: “Are we redistributing to support organizations, like ours? Or are we redistributing to support individuals, like the artists and cultural workers in our community?"

December 2020 Building the foundations of a Money Moving Coalition

The working group clarifies its intents and becomes a coalition, Cultural Solidarity Fund, only when it answers those questions. CSF is a coalition that redistributes money to artists and cultural workers without sacrificing organizations’ infrastructures, staff, or values.

The Cultural Solidarity Fund is primarily held by two people: Ximena Garnica, leader of LEIMAY, and Randi Berry, Executive Director of IndieSpace (formerly Indie Theatre Fund and IndieSpace). Ximena holds the vision of the coalition, rooted in her experiences as an artist of color and a self-produced artist working within and outside the non-profit structure, and Randi holds the financial administration, rooted in her community organizing experiences moving money. As women representatives of two artist women-led organizations, these partners recognize that co-holding stewardship of the coalition puts them in solidarity with one another — to continue holding the vision while another maintains, to continue building infrastructure while another relates.

From December 2020 onwards, all of the following organizers came in to support the implementation of CSF at one moment or another: Apollo Theater | Donna Lieberman; Bronx Arts Ensemble | Ellen Pollan; The Bushwick Starr I Lauren Miller; Caribbean Cultural Center African Diaspora Institute I Melody Capote; Dance Parade | DJ McDonald; Dancewave | Nicole Touzien; Mark Rossier | Individual; Hi-Arts | Hanna Stubblefield-Tave; IndieSpace | Randi Berry; LEIMAY | Ximena Garnica; Mark Morris Dance Group I Michelle Amador & Haley Mason Andres; Moore Opera | Cheryl Worfield; National Dance Institute I Juan José Escalante; New York Arts Live | Laurie Berg; New Yorkers for Culture and Arts | Lucy Sexton; NYC & Company l Carianne Carleo-Evangelist; Performance Space New York I Paula Bennett; Ted Berger | Individual; and Theater for a New Audience I Dorothy Ryan.

Together, the organizers set up a way to receive and redistribute money from a variety of donors (organizations, foundations, individuals) to the most marginalized people in the arts world (Black, Indigenous, People of Color (BIPOC), immigrant, disabled, d/Deaf, and trans and gender-nonconforming artists and cultural workers), implementing an amplified model for trust-based philanthropy utilizing tools engaged by IndieSpace and informed by the group to remove the subjective bias that can occur in the best of grants panels regarding the "validity" of an artist's work, to enable a rapid verification review of thousands of applications over days, a process that would have taken weeks if not months in more widely used grants review structures. It takes a week filled with meetings to develop the application’s open call and to discuss fundraising, allocations, applications, documentation, and storytelling infrastructure that comes with this work.57

February 2021 Raising the money

Unlike artist grant funds that begin with access to a pool of money, CSF had to find the funds it wanted to redistribute. CSF begins with a challenge grant of $25,000 from IndieSpace, recategorized from a previous grant from BroadwayCares/Equity Fights Aids. By February 2021, the first solicitations to match this challenge grant are made. By February 25, the amount raised is nearly $117,000.

February 26, 2021 Beginning to redistribute the money

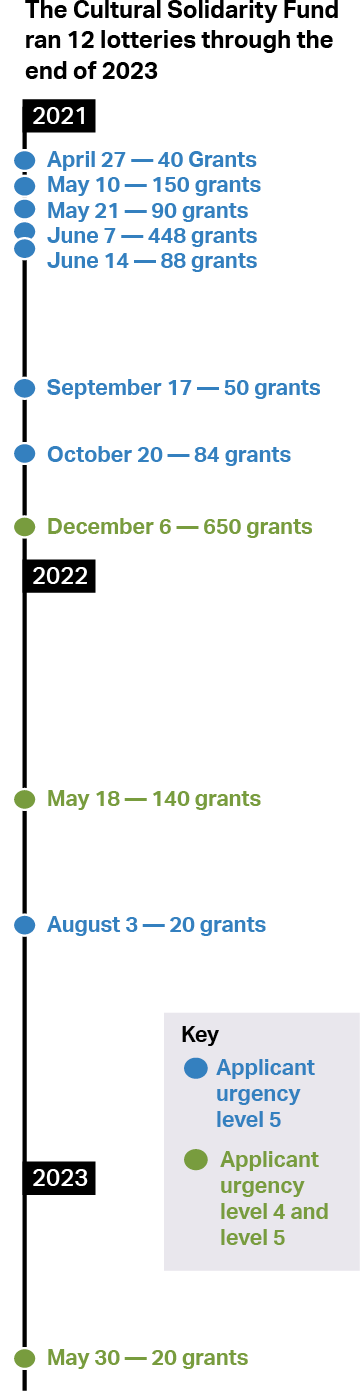

Applications for the fund open at 9:00AM EST on February 26, 2021. The application is open for one week and 2,722 artists and cultural workers apply. CSF uses a lottery structure to select grant recipients. There are a total of 12 lotteries, reaching 2,030 grantees.

As grants are redistributed, CSF continues to receive more donations, from foundations, organizations, and individuals.

May 1, 2022Sunsetting by saying: “It’s still not enough”

Over two years into the pandemic, the organizers of the Cultural Solidarity Fund begin to think about sunsetting the fund. The organizers reaffirm their commitment to funding all applicants in a public statement:

“CSF re-surveyed all remaining applicants and learned that 385 of them are still in urgent need of financial support. The Cultural Solidarity Fund remains steadfast in its commitment to meet this need with a trust-based approach to mutual aid that demonstrates a collective response to the hard lessons learned by attempting to address the emergencies occasioned by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Inspired by the opportunity to meet the needs of every applicant, CSF launches ‘Art Worker Solidarity: No One Left Behind’. From May 1 to August 31, 2022, CSF must raise $250,000 to close its initial commitment to those who serve us.”

— Cultural Solidarity Fund 58

Yet, the flow of donations to support this work slows. The mindset of a “new normal” has returned many to old ways: scarcity being the overarching theme. As funders stop funding redistribution efforts, other large institutions also step away from their support.

As CSF organizers dealt with a decrease in funding, they looked to efforts like this report, which came with a grant of $150,000 from Mellon Foundation, to sponsor 204 applicants’ grants. Still, the organizers hesitated to take on this money and use some of it for research or paying themselves. As the dominant economy seems to signal that CSF must end without funding all of its applicants, the organizers stand tall.

Tomorrow, onwards Moving beyond regranting and towards redistribution

Today, the spirit of the Cultural Solidarity Fund carries on. While the elite, rich, and the continually favored return to their new normals, CSF and others practice resistance.59 Resistance in 2024 looks different — it calls for more from some people (redistribution of power, resources, wealth from those who have) and less from others (rest for organizers, investments in maintenance and care). Where will we all go from here?

The system was built without us and against us.

The same Black, Indigenous, People of Color, immigrant, disabled, d/Deaf, queer, trans and gender non-conforming, and working class communities continue to be left out before and during crises. Why? Because the current economic system is not built to sustain the existence of the global majority. In the U.S. especially, we can draw this to two root and compounding causes: Racial Capitalism60 and Settler Colonialism.61

For centuries,62 Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) communities have had arts and culture-bearers at their core. Creatives build systems for thriving that prioritize the equitable distribution of resources and sustain community. Yet the dominant cultural ecosystem follows the same rules of the system it lives within. It puts profits over people, and it prioritizes Whiteness, class privilege, ableism, heteronormativity, and patriarchy.

In this system, a city like New York City is especially primed for inequity, drawn more explicit by its positioning as a cultural capital for nearly a century.63

- New York contains 26% of U.S. arts institutions, 37% of the country’s galleries, and 16% of its arts nonprofits.

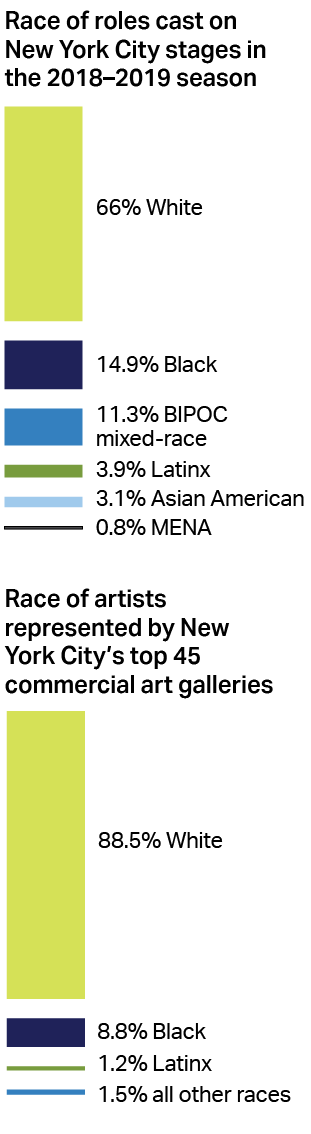

- While 32.1% of New York City's population is White, 60% of all roles on the city's stages in the 2018-2019 season went to White actors.64

- In New York City's top 45 commercial galleries, 88.5% of represented U.S. artists are White. The most underrepresented are Latinx artists, who make up 1.2% of represented artists, though the Latinx community is the largest minority group in the U.S.

- It’s simultaneously about class and education: 19% of represented artists graduated from Yale,65 a school that is a 50% White.66

The origins of the Cultural Solidarity Fund and of the U.S. cultural economy begin with the weaving of these two compounding historical threads, of Settler Colonialism and Racial Capitalism. CSF follows the work of many ancestors to build and dis-organize67 against this system.

COVID-19 lays stark inequities bare.

The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic hurt everyone — it was an abrupt transition to a reality few were prepared for, including long-standing institutions of the art world.68 COVID-19 reminded us that the privileges that keep us from precarity can often easily be taken from us, and that few people truly have access to stability through and beyond crises. Universal experiences of loss during the COVID-19 pandemic united people.

Even large arts and cultural organizations experienced this loss. Nearly 90% of all museums across the world (over 85,000) shut down, at an estimated cost of $5.5 billion across the arts and culture sector by May 2020.69

“COVID brought a set of universal conditions where our civic identities could once again compete with our often all-encompassing, if not always acknowledged, consumer identities… COVID’s conditions brought vulnerability and mutuality back into our relationships.”

— Mario Lugay, The Glorious Pull of Political Openings

“COVID hit us all. It hit communities of color harder than everybody.”

— Sadé Lythcott, CSF Donor

Individual artists and cultural workers have less access to safety nets than organizations. An April 2020 survey from Americans for the Arts70 found that:

- 80% of individual artists and cultural workers did not have recovery plans

- 36% only had savings to cover three months of experiences before COVID-19, 28% had no savings prior to COVID-19, and 53% have no savings now

- 31% also work outside the industry; of those, 49% faced furlough or unemployment

- 80% felt a decline in their ability to generate revenue

- 66% couldn’t access the resources they needed to make creative work

Traditionally, there are three dominant models that financially support individual artists: unions, employment, and freelance. All three models failed to fully protect individual artists during the pandemic. For example, the Actors Equity Association represents roughly 51,000 stage actors and managers, but, on Broadway alone, 1,100 of them lost work once the pandemic began.71

Employment in the arts and culture industry was precarious during the COVID-19 pandemic.72 Between April and July 2020, the Brookings Institution estimated cumulative losses of 2.3 million jobs in creative occupations.73

Several CSF organizers witnessed the increased levels of unemployment first-hand as they ran their own organizations.

Arts and cultural workers are over three times as likely to be self-employed,74 and more often work part-time or multiple jobs.75 Even before the pandemic began, independent creatives found it difficult to secure long-term or consistent income.76

“What if these unions aren’t the way forward for us anymore? What if SAG is not it? What if Actors Equity doesn’t have my back? And that’s been making me think of where we might find that, if we expand, maybe that’s what CSF can be or be a portal to.”

— Moira Stone, CSF Donor

Black, Indigenous, People of Color (BIPOC), immigrant, disabled, d/Deaf, queer, trans and gender-nonconforming, and working class individuals were already severed from safety nets that could protect them in and beyond times of crises.77 Between January 2020–August 2021, White workers unemployment rates were 1%, while “Black, Indigenous, Asian, and multiracial respondents collectively averaged unemployment rates about 6% higher.”78 Hispanic survey respondents faced more unemployment than non-Hispanic survey respondents; disabled respondents averaged unemployment rates “three to four percentage points higher over the period of January 2020 – August 2021. That figure increases to about 12 points if looking only at the first six months of 2020.”79 Within the gender binary, women experienced higher levels of unemployment before the pandemic; our siblings outside the gender binary likely faced equal or worse disparity.

New York City’s positioning as a creative hub did not shield its artists and cultural workers from pandemic-driven loss. Between March and April 2020, 52,100 people lost employment in the arts and culture sector. New York City saw a 69% decrease in employment between July 2019 and July 2020.80 Over the same time period there was a 1208% jump in unemployment claims in the arts and culture sector, nearly twice as much as other industries’ unemployment rates.81

“I saw the evidence because all of these W2s got returned, but also all of these unemployment claims.”

— Dorothy Ryan, CSF Organizer

Acting on a political opening to redistribute resources.

While we have long known that marginalized communities experience deeper precarity, our sense of unity to resist and build hasn’t always been as strong (though it may have always been possible).82 Though the COVID-19 pandemic threw the world suddenly into crisis, communities found ways to support each other. It offered what Mario Lugay calls “a political opening” to reconsider the status quo and reflect on complicity. People responded by witnessing the intertwining of individual and collective pain, and translating it into action. 2020 saw a rise of multi-modal mutual aid groups,83 with more people on the street protesting and rallying,84 and with more expressions of gratitude for workers and work.85

“A culture born out of an extractive economy — steeped in individualism, consumerism, scarcity and competition — casts long shadows and causes doubt... Then a political opening arrives...”

— Mario Lugay, The glorious pull of political openings

At the federal level, this political opening launched programs like the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) loans and the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act to launch. These initiatives financially supported full-time and freelance workers as they lived through the pandemic.86

The art world also used this political opening to invest in ecosystemic care. One funder of the Cultural Solidarity Fund talked about how arts organizations played more than just a professional role in the community throughout the pandemic.

“I felt a really acute need to be action oriented during a time when things felt really uncertain.”

— Nicole Touzien, CSF Organizer

“Art service is typically about the administrative backend of helping artists create artistic products or artistic experiences. During the pandemic, the nature of art service changed to one of social service. Grant applications became processes where you were a social worker, and where you were reading stories of loss and need that were way beyond the scope of [what we were used to].”

— Alejandra Duque Cifuentes, CSF Supporter

New York City is a uniquely dense cultural hub, so its struggles are at a larger scale than other cultural hubs across the U.S. As a result, artists and cultural workers in New York organize both with more resources than other cities and in deeper scarcity. New York City received more funding than other regional art worlds, despite the fact that the most marginalized communities in the U.S.’s national arts and culture ecosystem are the communities outside of cities, urban hubs, and located in the South or in Indian country. The American Rescue Plan Act for the Arts87 awarded 85 grants to New York state (including 73 to New York City), totalling an $8.8 million investment in this regional art world, much higher than the average of 10 grants per state.88 Even this wasn’t enough and resources still remained out of reach for the most marginalized.

Across time, marginalized communities and allies have always developed tactics to redistribute whatever resources they have access to and control over. COVID-19 carried these tactics into the mainstream. Communities across the world were united by a sense of responsibility that made it more possible and sustainable to share space, supplies, energy, information, and money.

One example of redistributing resources in the New York City cultural community is Culture@3PM, a daily Zoom call where arts organizations could share and receive information and energy.